Preached on the Fourth Sunday of Advent (Year A), December 21, 2025, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Seattle, Washington by The Reverend Stephen Crippen.

Isaiah 7:10-16

Psalm 80:1-7, 16-18

Romans 1:1-7

Matthew 1:18-25

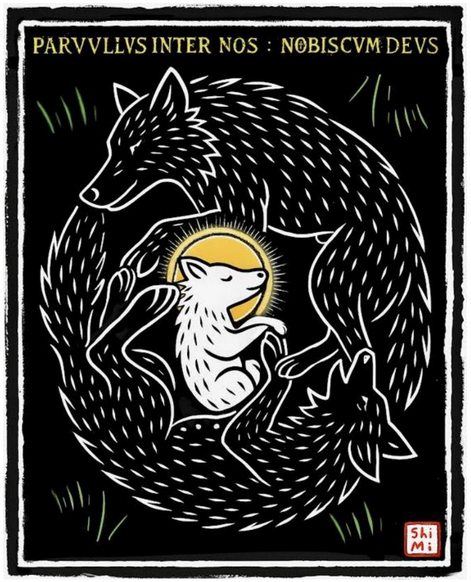

A little one among us: God-with-us, by Claire Fox aka Shimi

“Those who speak do not know. Those who know do not speak.”

This is a Taoist saying, attributed to the philosophical tradition of Lao Tzu. But we Christians pray alongside a few saints who seem to have lived by this maxim, first among them Joseph of Nazareth. Joseph says not one word in our scriptures. I like to think of him as the patron saint of my parents’ generation – the Silent Generation, the masters of endurance, the artisans and scholars and workers who know a lot, but say very little.

Joseph said nothing at all, at least in our hearing, but he certainly listened. He paid attention to four dreams, dreams that counseled but also challenged him. One: Joseph listened when God’s messenger reassured him that he and his controversial bride would be alright, that he should marry her, and that he should name her son. (By naming the child, Joseph became his legal guardian, saving his – and his mother’s – lives.) Two: Joseph listened when God’s messenger encouraged them to run for their lives – making them refugees. (In our time, we know a lot about refugees.) Three: Joseph listened when God’s messenger said it was safe to return home. And Joseph listened a fourth time when God’s messenger warned them to settle not in the political tinderbox of Judea, but in the tranquil Galilee region.

In all of this listening, Joseph comes into focus for us. Saying not one word, his identity and character nevertheless become clear: Joseph is faithful and obedient; Joseph is brave and dauntless; Joseph is a refugee and a caregiver. Joseph is a low-income survivor of state-sponsored terrorism who experiences homelessness. Joseph is a virtuous person, a discerning person, a person of integrity, a person who listens, a mensch.

Joseph is one of our best exemplars. If we want to follow his example, if we want to truly listen like Joseph, then first we need to get quiet. At St. Paul’s, we encourage quietude. Our organist counts off ninety seconds of silence after the second reading. After a sermon, and after the distribution of Communion, we keep a little more silence. We’re not in a hurry. Our liturgy forms us to be people who know and don’t speak.

But the problem with quiet listening is all of those disturbing dreams. “Get up, Joseph,” says God’s messenger. “Flee to Egypt.” Then: “It’s safe now, you can return; but wait! Take your young family around the dangerous city. Keep going another hundred and fifty kilometers – get yourself to Nazareth, up in the north.” (God’s messenger doesn’t explain how Joseph will feed his family on these long treks. Were they in Egypt long enough for the infant to become a toddler? Maybe, but it’s not much easier to travel with a toddler than an infant when you’re on the run from political oppression. Harder, even.)

And so it goes for us, as we get quiet, as we listen. God’s messenger sends us in mission. God’s messenger disrupts our comfort, our certitude, our contentment. And God’s messenger appears in various ways, unpredictable ways. Dreams? Sure. But sometimes we listen to our bodies; we listen to our neighbors; we listen to our friends; we listen to our enemies. When my therapist asks me where in my body I feel a feeling, I groan: I rarely know how to answer this. I wasn’t raised to listen in that way. I need help listening to my body, which carries feelings both hard and kindly in places just out of my conscious reach.

And listening isn’t always as straightforward as receiving a message and then doing as instructed. Listening is discernment; listening is a heightened consciousness; listening is a stance of humility, openness, and curiosity. Listening is a form of intelligence. And so… Saint Joseph is great, but we may need a few more exemplars.

Mary Magdalene listened. At first blush she thought she was meeting a gardener. Then she listened, and when he spoke her name she knew instantly who he really was. Mary the mother of Jesus – Mary the spouse of the listener Joseph – listened carefully to God’s messenger, and responded with a “Yes” to the messenger’s immense challenge, a challenge that would transform her life, and her destiny; a challenge that would painfully pierce her heart. Saint Thomas, another Advent saint – in fact, today, December 21, is his feast day – St. Thomas listened, no matter how impulsive he might have been when he first returned to rejoin the movement. When the risen Jesus appeared to him and invited him to touch the wounds, Thomas didn’t need to. He was paying attention. His mind and heart were open. He took one intelligent look at the risen Jesus and, for the first time in human history, affirmed that Jesus is God.

We have these grand exemplars. We cherish them. But we have some local ones, too. Since August 7, we have watched with deepening grief as five of our friends have died in the peace of Christ. They were, all of them, holy listeners. Tom listened gently to God with a kind and gracious heart. John listened intelligently to God with keen insight, creativity, and wit. Ellen listened to God faithfully with the fortitude of a wise and trustworthy friend. Robin listened seriously to God with a determination to work hard and make a strong difference in this community. And Prue listened courageously to God as a gardener, launderer, and laborer, listening with her hands, wearing out her shoes, tuning in to all the endless, often unnoticed needs of this community.

They all, like the great saints before them, are listening on a spiritual plane. They do not just hear about problems and respond to human needs; they discern what is best. They ignore anything irrelevant. And yet, their listening – our listening – does not always form Christians into the easiest people to know. When we are listening carefully, we can really pack a punch: burning with mission, we lead others into the arena. Frayed with impatience, we tap our feet with holy determination to lead, to fix, to heal. Blessed with courage, we can be daunting in our zeal for honesty, for truth, even for revolution.

In all of this, God is Emmanuel: God is with us. Like Joseph of Nazareth, that great dreamer, God draws astonishingly close to us, even into our dreams, to enlighten our minds and break open our hearts. We labor here under God’s power, with God’s compassion, on God’s errand. We receive wisdom, and strength. God gives us grace and skill to judge wisely, to serve skillfully. We are raised up in power, for the life of the world.

I want to close with one more Taoist treasure, this time a little story told by the Taoist sage named Lieh-Tzu, found in his eponymous book, Lieh-Tzu: A Taoist Guide to Practical Living. The story is a parable about discernment and wisdom; about sound judgment and shrewd skill; about who we might eventually become when we really get quiet, and really listen. Here’s the story:

Duke Mu of Chin said to Po Lo: “You are now advanced in years. Is there any member of your family whom I could employ to look for horses in your stead?” Po Lo replied: “A good horse can be picked out by its general build and appearance. But the superlative horse – one that raises no dust and leaves no tracks – is something evanescent and fleeting, elusive as thin air. The talents of my sons lie on a lower plane altogether; they can tell a good horse when they see one, but they cannot tell a superlative horse. I have a friend, however, one Chin-fang Kao, a hawker of fuel and vegetables, who in things appertaining to horses is nowise my inferior. Pray see him.”

Duke Mu did so, and subsequently dispatched him on the quest for a steed. Three months later, he returned with the news that he had found one. “It is now in Shach'iu,” he added. “What kind of a horse is it?” asked the Duke. “Oh, it is a dun-colored mare,” was the reply. However, someone being sent to fetch it, the animal turned out to be a coal-black stallion! Much displeased, the Duke sent for Po Lo. “That friend of yours,” he said, “whom I commissioned to look for a horse, has made a fine mess of it. Why, he cannot even distinguish a beast's color or sex! What on earth can he know about horses?” Po Lo heaved a sigh of satisfaction. “Has he really got as far as that?” he cried. “Ah, then he is worth ten thousand of me put together. There is no comparison between us. What Kao keeps in view is the spiritual mechanism. In making sure of the essential, he forgets the homely details; intent on the inward qualities, he loses sight of the external. He sees what he wants to see, and not what he does not want to see. He looks at the things he ought to look at, and neglects those that need not be looked at. So clever a judge of horses is Kao, that he has it in him to judge something better than horses.”

When the horse arrived, it turned out indeed to be a superlative animal.

***

This particular translation of the Taoist tale about the horse is found in J.D. Salinger’s novel, “Raise High the Roofbeam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction.”