Preached on the Fifth Sunday after the Epiphany (Year A), February 8, 2026, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Seattle, Washington by The Reverend Stephen Crippen.

Isaiah 58:1-9a

Psalm 112:1-9

1 Corinthians 2:1-12

Matthew 5:13-20

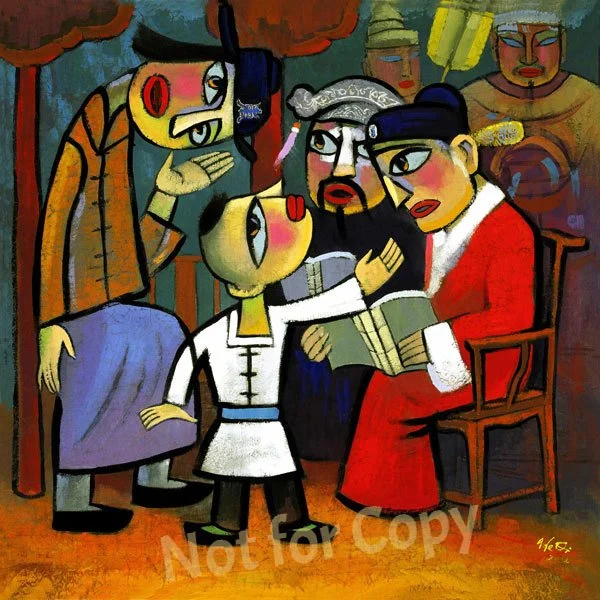

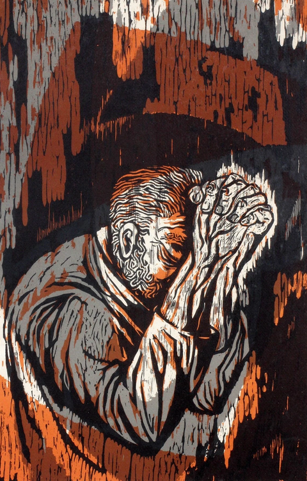

Light of the World, by art4prayer

A reading from the song lyrics of the Paula Boggs Band. (Paula Boggs is a Seattle-based musician and a member of this congregation.)

When life takes a turn for worse

remember this little verse:

we all fall down.

Let's not make it even worse.

There's more than enough to curse.

We all fall down, don’t you worry.

No matter how high we climb,

life will find a way to kick our behinds.

And so, I am no better than you,

Christian, Muslim, Buddhist, Jew,

we all fall down.

Even your boss the jerk, chases skirts,

and thinks he's cool as Captain Kirk —

he will fall down, don't you worry,

cuz just when we think we’ve arrived,

something really crappy breaks our stride.

We all fall down, don't you worry.

Guaranteed! We all fall down.

Believe me! We all fall down.

Here ends the reading.

Sometimes it helps to just admit it, just accept it, just come right out and say it: we are all fallible, we all make mistakes, we’ll never measure up, life kicks our behinds, we all fall down. But I’m eager to remind you that this bracing acceptance of reality is cherished in our tradition. We Episcopalians often like to say that we are Catholic but also Protestant, and that we hold both identities together in creative tension. So let’s allow the best of our Protestant tradition to reassure us: Protestants admit freely that humans are error-prone, and that only by God’s grace are we saved from the dreadful future of our own design.

So… relax. We all fall down. No need to worry about whether it will happen to someone like your skirt-chasing boss: he will fall down. And no need to worry about all the rest of us falling down. We will. It has occurred; it will occur.

I offer all of this as a preamble to the daunting Good News we hear today, news that tells us first how great and lovely we are, and second how high God’s standards are for us. Jesus begins by calling us “salt of the earth” and “light of the world.” This is high praise! As salt, we season the world around us with our insights, with our trustworthiness, with our strong and refreshing presence in the worlds of home, neighborhood, church, and public square.

Salt-of-the-earth types are found at protests: just look at the hordes of them on the streets of Minneapolis! Salt-of-the-earth types are stocking our pantry shelves and pulling our wagons around Uptown. They’re hosting coffee hour and bringing Communion to our homebound members and teaching Godly Play lessons to our children and digging graves for our friends. Salt-of-the-earth types are practicing courage and ethics in their relationships; they’re raising children with insight and patience; they’re showing up for their co-workers and friends; they’re voting for change and advocating for those in peril.

And then there are the light-of-the-world types, dazzling us with their intellects, brightening our days with their poetry or their paintings, showing us the way through the wilderness as torches of wisdom, pillars of encouraging fire in the night. And maybe the salt and light come together in one person — maybe in you. Are you a salt-and-light person? Jesus seems to think so. (No pressure or anything.)

Salt and light came together recently in another playful yet prophetic way. Christy Drackett, one of our members, texted me yesterday with a meme that was just created by someone in New York. It says this: “In this Sunday’s Gospel, Jesus calls us to be salt and light. Looking out my window in New York City, I think… both of those things melt ICE!”

Yes. Yes they do. Salt-and-light people melt the powers and principalities that occupy cities, abuse children, execute innocent people, and separate families. I would only correct one thing in that clever meme: Jesus does not “call us” to be salt and light. He says that we already are salt and light. (Again, no pressure or anything!)

And then, piling on, Jesus reminds his followers that his movement is not a relaxation of the Torah commandments. “Whoever breaks one of the least of these commandments,” he says, “and teaches others to do the same, will be called least in the kingdom of heaven.” Then, after this section of the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus launches into a series of “You have heard that it was said, but I say to you” statements, and in each of them, he turns up the heat on us.

We shouldn’t murder, for that is what we are taught in the Torah. But Jesus turns up the heat: we can’t even be murderously angry at one another. We shouldn’t betray our spouses with adultery, for that is what we are taught in the Torah. But Jesus turns up the heat: even the casual betrayals common in his time, particularly those that demeaned women, were taboo in the Jesus Movement. Jesus is determined to remind us that his movement is serious, and that we — his salt-and-light followers — need to bring our A game.

Which brings me back to Paula’s song I love so much, the song that reminds us not to worry, because we all fall down. Jesus calls us salt and light, and then he turns up the heat on us: being a Christian is serious business. Much is expected of us. But hold up for a second. Let’s look again at people we know who are salt-of-the earth people, or light-of-the-world people.

I do not know one person I would call “salt of the earth,” or “light of the world,” who is not salty or enlightening because they fell down; because they are fallible.

How can you be a salt-of-the-earth visitor to someone who is sick or dying? Only by empathizing with them by drawing on your own history as someone who gets sick, or by drawing on your own self-awareness that you are mortal, and that one day you also will die.

How can you be a light-of-the-world protester for the rights, freedom, and dignity of others? Only by acknowledging the deep darkness people experience at the hands of our government, and relating it to your own experiences of glum sadness and dim despair.

How can you be a salt-of-the-earth neighbor, or co-worker, or spouse, or wise elder? Only by empathizing with your neighbor’s errors, your co-worker’s shortcomings, your spouse’s blind spots, or the times without number when you as a well-intentioned but fallible human have messed things up, or let someone down, or just blown it because you were just having a terrible, horrible, no-good, very bad day.

“You are the salt of the earth, and you are the light of the world,” Jesus says, and then he gives us our daunting assignments in this community of faith. But he gives us these assignments, not flawless machines who succeed without failure, without error, without the slightest flaw. We are mortal and vulnerable; we are anxious, sometimes short-tempered, and often simply absurd. But that is in our essence as salt-and-light people. It is what makes us good at all of this.

And God has our back. Remember the Protestant wisdom about grace saving us, not our own works? It’s God’s grace that saves us, God’s grace that sends us, God’s grace that brings all of our efforts to a good end. We heard this once again today in a stirring speech by the prophet Isaiah. (Sidebar! Do you know how many of God’s prophets were fallible, shortsighted people who resisted the call and made a ton of mistakes? All of them.)

Isaiah sings to us great words that rival even that great prophet of our time, Paula Boggs. Isaiah sings to us, the folks who will fall down, and he sings great reassurance to us about God having our back: When we imperfectly do the work of loosening the bonds of injustice, letting the oppressed go free, sharing bread with the hungry, bringing the homeless poor into our house, and covering those without clothes, then, Isaiah sings, our light (remember, we’re light!) — our light will “break forth like the dawn, and our healing shall spring up quickly”...

Your vindicator shall go before you,

[and] the glory of the Lord shall be your rear guard.

Then you shall call, and the Lord will answer;

you shall cry for help, and [God] will say,

“Here I am!”

Click here to hear the Paula Boggs Band song, “We All Fall Down.”