Preached on the Last Sunday after the Epiphany (Year A), February 15, 2026, at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church, Seattle, Washington by The Reverend Samuel Torvend.

Exodus 24:12-18

Psalm 2

2 Peter 1:16-21

Matthew 17:1-9

There is a striking parallel in the readings appointed for this day, this last Sunday before Ash Wednesday and the beginning of Lent. In Exodus, we hear that Moses went up Mount Sinai and that for six days a cloud covered the mountain in which Moses behold the glory of the LORD, God’s glory, God’s presence, likened to a brightly burning fire. And there for forty days, Moses remained with God. In Matthew, we hear that after six days – six days after he announced that he would suffer in Jerusalem for his teaching and his actions – Jesus and three of his followers climbed to a mountain top where God’s glory as a cloud surrounded Jesus whose clothes became dazzling white, whose face was as bright as the burning sun. Attending Jesus were Moses and Elijah, two prophets who had encountered God on a mountain, what the ancients believed was the highest a human could travel to encounter the divine. This event in the life of Jesus has come to be called the transfiguration, a word not often heard in common speech, one that refers to the change in one’s appearance or a change in one’s nature.

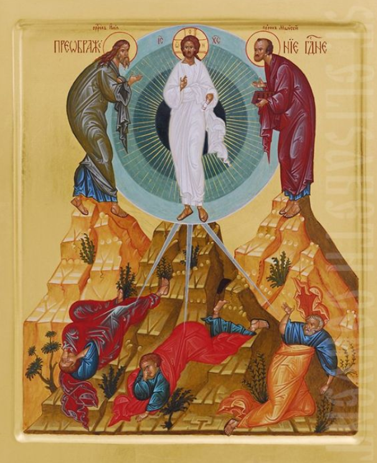

My mother of blessed memory was trained as an art educator. She would frequently find in one of her many art books, a painting or mosaic of the gospel reading appointed for a Sunday and invite us to see the artist’s interpretation of the story, an interpretation that might be different from the one we heard from the preacher that day. In 1971, some fifty-five years ago, she gave me this little book entitled An Introduction to Icons, a simple introduction for western Christians unfamiliar with the sacred images so prevalent among eastern Christians. This little book ignited my interest not only in the sacred art of Eastern Orthodoxy but also its liturgy and its theology. Among our Eastern Orthodox friends, the transfiguration of Jesus is called the Brightness of God, a title intended to highlight the Christian conviction that the presence of the divine is revealed in the human – what we confess in the creed concerning Jesus when we say or sing “God from God, Light from Light.” The Orthodox icon of the transfiguration [which you find on the cover of the worship program] depicts Moses (on the left) and Elijah (on the right) facing the Jesus in the center: his clothing bright white. But note how the artist has surrounded Jesus with three concentric circles at the center of which is a dark circle with many rays of light radiating outward from behind the dark circle – radiating outward to the two prophets and downward to the three followers struck by amazement at the vision.

Well, what’s up with that? Perhaps it has something to do with the Eastern Christian emphasis on Jesus Christ as the new or second Adam, an image inspired by St. Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians in which he writes that Jesus presents to us what it means to be a truly human being, living in God’s grace, and embracing the world with compassion. Needless to say, it is an image of light shining forth from within the human Jesus, the light of the divine. Indeed, in the liturgy of eastern Orthodox evening prayer, we hear this acclamation sung: “O Christ, on Mount Tabor, the mount of transfiguration, you transformed the darkened nature of the first human and filled it with brightness, making it godlike.” Well, to some that kind of language might sound so esoteric or so florid. After all, who among us imagines that we’re filled with the light of the godhead. I mean when I get up in the morning, struggling through the fog of sleep to find that first cup of coffee, I am hardly thinking about being godlike.

But I say: Hold on! The Orthodox title of this event – the Brightness of God – and the icon that portrays Jesus with light radiating through him and around him, and the evening prayer acclamation about what true humanity looks like all point to one thing, to this core Christian conviction and sacramental mystery: that ordinary things – water, oil, bread, and wine – can hold, bear, reveal extraordinary things; that ordinary human beings – that you and I – are capable of revealing the extraordinary presence of God in our lives. Or say it this way: we are called as Christians to bear the brightness of God in our lives, in our words and in our actions. It may be a stretch for some of us to imagine that we are becoming godlike – and let’s be clear: there are far too many people in our nation who imagine that they are gods with absolute power over others.

But to live as the brightness of Christ in this place and in this frequently darkened time: I think we know what that means. You and I do not spread disinformation, lies, or malicious gossip – rather we tell the truth but do so with love; you and I do not speak of others in a demeaning manner – rather we strive to respect and honor the God-given dignity in every human being, even those we might find strange or oddly eccentric; you and I do not remain silent in the presence of injustice and violence – rather we protest such travesties and strive for justice and peace; you and I do not expect to be served by others as if the world circles around us – rather we seek to serve Christ, especially in the poor and vulnerable, the lonely and the forgotten. Dear friends, this – this, I think – is what the brightness of Christ might look like in you and me.

As a Roman Catholic priest, I was taught to pray this prayer while adding water to the flagon of wine at the altar in preparation for the eucharistic liturgy: “By the mingling of this water and wine, may we come, O Christ, to share in your divinity as you humbled yourself to share in our humanity” – the water of our humanity mingling with the wine of his divinity, becoming one. The intent of the prayer and indeed of the communion was to make clear, is to make clear, that you and I are being nourished in the Brightness of Christ’s life. The only question is: will that sip of brightness shine forth in our words and deeds and so give others what our suffering nation desperately desires: why, a sense of hope?